Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Special Offer from PM Press

Now more than ever there is a vital need for radical ideas. In the four years since its founding - and on a mere shoestring - PM Press has risen to the formidable challenge of publishing and distributing knowledge and entertainment for the struggles ahead. With over 200 releases to date, they have published an impressive and stimulating array of literature, art, music, politics, and culture.

PM Press is offering readers of Left Turn a 10% discount on every purchase. In addition, they'll donate 10% of each purchase back to Left Turn to support the crucial voices of independent journalism. Simply enter the coupon code: Left Turn when shopping online or mention it when ordering by phone or email.

Click here for their online catalog.

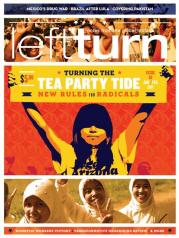

This is What a Tea Party Looks Like

However they felt about Barack Obama’s presidential campaign two years ago, activists on the Left agreed about one thing: any real gains to be made under an Obama presidency would depend on pressure from the grassroots after the voting was over. Unfortunately this consensus did not actually lead to such a mobilization. Major labor unions descended into embarrassing conflicts with each other instead of seriously fighting for labor law reform. Mass movements against war and for immigrant rights lost their ability to put people in the street, and the massive outpouring of democratic hopes that dealt the Republicans their soundest defeat in generations was channeled into little more than fundraising spam emails from DC. The first few months of the disappointing Obama administration could hardly surprise anyone familiar with the words of Frederick Douglass—lacking demand, power conceded very little indeed.

However they felt about Barack Obama’s presidential campaign two years ago, activists on the Left agreed about one thing: any real gains to be made under an Obama presidency would depend on pressure from the grassroots after the voting was over. Unfortunately this consensus did not actually lead to such a mobilization. Major labor unions descended into embarrassing conflicts with each other instead of seriously fighting for labor law reform. Mass movements against war and for immigrant rights lost their ability to put people in the street, and the massive outpouring of democratic hopes that dealt the Republicans their soundest defeat in generations was channeled into little more than fundraising spam emails from DC. The first few months of the disappointing Obama administration could hardly surprise anyone familiar with the words of Frederick Douglass—lacking demand, power conceded very little indeed.

Meanwhile, the national debate around a package of minor adjustments to the country’s broken healthcare system brought an ugly plot twist to contemporary politics. It remained true that pressure and mobilization would shape the Obama’s legislative agenda—but the only political actor to show up in force for the fight was the Right.

Astroturf or Mass Movement?

It would be hard to imagine a more thorough public rejection than the one the Republican Party received in the 2006 and 2008 elections. Years of conservative extremism, buffoonish incompetence and fundamentalist hypocrisy seemed to somehow aggregate, peak, and crest all at once in a tidal wave of imperial defeats, urban disasters, evangelical sex scandals and the biggest economic collapse in two generations.

The election of someone like Barack Obama, so unthinkable just a few years prior, symbolized not just America’s disgusted turn away from the hapless criminality of George W. Bush’s presidency, but progressive changes on the horizon. The statistical decline of America’s white majority and the wholesale abandonment of conservative Christianity by young people seemed to indicate that the American Right was not just losing an election, but the entire future.

While the Republicans may one day accommodate themselves to the very different country the United States is becoming, for now their reduced size and popularity has enabled the Far Right to tighten its grip on the party. But acknowledging the continued disdain much of the country feels for the Republicans, the Right has simultaneously avowed their independence from the corruptions of partisan politics, and restructured themselves to appear as the sort of grassroots movement of independents best able to capitalize on recession and crisis.

When a little-known cable business news entertainer named Rick Santelli erupted in February 2009 in a rant against the new president’s attempts to stabilize the collapsing home mortgage market, accusing the government of “bailing out losers” and vowing to hold a “Tea Party” against government spending, few realized they were witnessing the opening salvo of the re-branded American Right’s newest war for political power. Santelli’s speech met with an instantaneous proliferation of Tea Party web sites and organizations. Asserting their distance from the still-hated Republicans and branding themselves with the fond mythos of the Boston Tea Party, the Right re-positioned themselves overnight—one of the more skillful ju-jitsu moves in modern political history.

Not everyone was fooled, of course—the provocative webzine, The exile, quickly published proof that Santelli’s demagogic call for class war by the wealthy came not from his own greedy imagination, but rather the shadowy world of Republican and libertarian politicos. Scouring Google cache records for evidence from deleted web histories, they and other progressive bloggers, determined Santelli was merely the front-man for the launch of a protest campaign developed over the past year by Republican activists at FreedomWorks. Former congressional Republican leader Dick Armey loomed over the just-add-water movement—less Sam Adams and more a sinister Mad Hatter, boldly defying logic with his claims that Obama’s economic stabilizations (and not the past decade’s war-profiteering, corporate welfare, and tax cuts for the rich) were endangering the country with debt.

Corporate PR firms long ago perfected the art of staging fake grass-roots campaigns (called “Astroturf” in the business) to advance their clients’ agendas. But critics of the Tea Partiers who assert it is simply a cardboard cutout fake movement fronting for the rich miss an important distinction between it and normal Astroturf groups, which often have no members and mainly exist on paper: the Tea Party, as the new vehicle for America’s Right, has genuinely gained millions of very real supporters.

The Right has long comprised the largest bloc in our country’s body politic—anywhere from 25-50 percent of the electorate. Opinion polls over the past two years have found large segments of the country supportive of the anti-tax Tea Parties—begging the question of whether something can accurately be called a “fake” movement, if close to half the country agrees with it.

Funding Reaction

A recent investigation in the New Yorker traced the Tea Party’s deep pockets to Charles and David Koch, the billionaire libertarian aristocrats who run the country’s second-largest private company, chemical and energy conglomerate Koch Industries. But searching for puppetmasters is easier than squarely facing the millions we might rather dismiss as marionettes. After all, campaigns to expand the wealth and power of the rich will always, by definition, have access to near-limit- less funding from their corporate constituents. But only in a political climate as conservative as the United States’ can such campaigns authentically take on a mass character.

The American Right comprises millions of people. From the day-shift manager of a fast-food joint whose politics lie not with his current bank balance but with his aspirational faith in achieving future riches to the millions of suburbanites, millionaires on paper, who fixate more on the possibility of losing such status to tax collectors than in one of the crashes our financial system now mass-produces.

And while a NYT/CBS poll found that Tea Partiers were wealthier and better-educated than average, there are also signs that plenty of the anti-tax protestors are not exactly Harvard MBAs—signs like, well, their protest signs! Who hasn’t been emailed a humorous picture (or ten) of a misspelled placard demanding the “Fediral govrment stay out of Medicare”? The left, with its preprinted graphic-designed signs, might even learn a lesson from the way the mangled language of the Tea Party (or George W. Bush) can be perceived as markers of “just plain folks” authenticity in a country where the average person reads at an eighth grade level and knowledge workers (not CEOs) are vilified as elitists.

The Tea Party clearly includes many people whose right-wing passion outstrips their formal education and they are not shy about showing it. The protests are as economically inclusive as they are racially exclusive—“independent” voters, who are actually doctrinaire conservatives, a mass movement with deep roots in the exurban middle class but tentacles extending from libertarian billionaires to downwardly-mobile Baptists, from anti-union union members to Upper East-Side Islamophobic bloggers.

Family Values

I happen to have some personal experience with this sort of economic diversity on the Right. One of my parents grew up quite poor in an urban, Eastern-European family of unionized industrial workers, but moved both rightwards and over the county line in the 1980s. These moves might charitably be described as a reaction to the disorder and chaos of America’s big cities in the 1970s, but in truth also involved every sort of bigotry available to a white-flight suburbanite in the Reagan era. My other parent, from a family of suburban middleclass strivers, worked his way through law school and used his relative privilege and education to develop a more ideologically coherent freemarket conservatism and “Great America” nationalist militarism.

These parents’ pasts did not have much in common, but politically they fit together seamlessly in the Republicans “broad right.” They have always been mildly politically active, experiencing the entire tragic arc of the Bush administration, from triumphalism in 2000, to jingoist hysteria after 9/11, and eventually to the dismayed realization by the end of Bush’s second term that something had gone badly awry. After a brief retreat from politics altogether, they’ve rediscovered political involvement, in the Tea Party.

They are not “tricked” by social issues (a la Thomas Frank’s What’s The Matter With Kansas), nor are they truly afraid of mounting public debt, nor do they sincerely object to Bush or Obama stabilizing the financial system by bailing out failing banks and companies. Rather, they authentically hold a variety of values and beliefs that place them, along with many other Americans, well out on the right wing of politics.

Distrust of a black president with Islamic heritage and an extreme hatred of redistributive taxation are not mutually exclusive for them, just as they do not need to choose between American nationalism and Christian intolerance as primary reasons for hating Muslims. They come from different directions but arrive in the same political coalition, a large and historically dominant hard-Right that has responded to exile from power by reasserting its strength at the grassroots.

The F-Word

A middle-class movement funded by big business that speaks of purifying a nation’s honor tends to provoke the f-word word among leftists. Not just the expletive, but also the more obscene historical movement from the 1930s. But there are problems with using “fascism” as either descriptive label or conceptual framework for today’s Right (whether in its Tea Party packaging or any other mainstream political incarnation). The “classical” fascist regimes of World War II undertook crimes and genocides that are widely seen today as historic singularities, world-shaping horrors of such magnitude that rhetorical connection to contemporary rightists (whether a bonehead gang or anti-tax media maelstrom) seems out of proportion, unrealistic or even perhaps offensive.

Beyond that however, the vast gulf between the world of interwar Europe and America in 2010 can be instructive for gaining a sense of realism and proportion about our political predicament. In 1920s Europe, the frenzied apocalypse of world war had collapsed into inconclusive exhaustion; militarism and fundamentalist nationalisms were frustrated, not discredited. Socialists attempted a series of revolutions with varying degrees of success. Where capital survived, it faced massive left-wing labor movements; anti-capitalist ideas dominated the intellectual landscape. Fascism was a movement of the revolutionary Right against this insurgent Left.

The United States today is quite a different place—neither smoking ruin nor smoldering powder keg. Labor unions, Socialist parties, left-wing mass movements all have declined to near-extinction. Marxism barely clings to survival as an obscure quirk in academia; working people have responded to a generation of downward mobility not with rebellion but through consumer debt.

Not content with the demise of the specter of revolution, however, the American Right of the past forty years has advanced on and conquered reform. Conservative intellectual and Bush speechwriter David Frum once defined American conservatism’s historical mission as “stop the country’s slide towards social democracy,” and pronounced that mission as having ended in unambiguous success. In a world that has moved right, the United States stands at the vanguard’s edge. Even the basic elements of the social contract are increasingly rolled back. If revolution has faded into the mists of unthinkable impossibility, even reform itself seems to have joined it. But the millions of right-wing Americans who were politically molded by this long march—having by most measures inarguably achieved their goals—have declined to dissolve their movement and exit the stage of history. Without any real enemy left, the American Right has become something of an angry zombie, a golem that still stalks the land even when its task is done.

Still existing in the millions, with a vast movement apparatus, the dominant political party and the largest media machine in the world, the Right lurches about looking for new enemies in a somewhat bizarre and random fashion. One year they may label a mild, centrist, technocratic tweak to an antiquated part of the social apparatus as “socialism” and go on a hysterical rampage against it; the next they may fixate on their own pre-rational fears of a religious minority like Muslims or atheists. Some issues are entirely hallucinated, others are still in service to their historical paymasters in the Chamber of Commerce, and still others spring from eccentric conspiracy theories.

The Right’s campaign against Obama’s health care reform is one example of the rabid dog of the Right slipping its big-business leash. The Obama team’s priority was simply to get something very basic passed. To this end, they shaped a legislative package with the full participation of all the players in that hopeless broken and wasteful system. Not a single major actor in the Rube Goldberg contraption that is US healthcare was terribly dissatisfied with the mild package of modernizations and tweaks. Presumably the Obama team’s belief was that the Right would not fight hard against something business was happy with--but the opposite happened. Even with Pharma, the health systems, the doctors and the insurers all on board, the Tea Party still incited hysteria about a “socialist takeover” of American healthcare.

Facing the Golem

The existence of a durable right-wing bloc of roughly one-third of the country, with a demonstrated ability to stop even mild reforms and a penchant for unpredictable rage, raises some questions for people concerned with social justice. This hard Right is much larger than anything that could credibly be called a Left in America, and certainly more motivated than the moderate or apolitical folks who make up the rest of the bandwidth.

So the large majority of society that does not share the Right’s reactionary values is confronted by the immediate strategic question of how to keep them out of power. The classic formulation of this conundrum is the 2000 Bush-Gore election, when many believed that ill-considered competition between Democrats and Greens in swing states contributed to the disputed election result that Republicans used to seize the Presidency. Eight years of George Bush was a hard lesson for many progressives and radicals that when dealing with vast amounts of power, even small differences between mainstream political parties can translate into quite large results.

But popular front-style cooperation to keep the Right out of power is not the only problem America’s Right poses. More generally their success has derived from a shifting of the political center of gravity in the US quite far to the right on most issues. Moving that football back down the field in the other direction would benefit people from across the political spectrum—from milquetoast liberals to fire-breathing revolutionaries—and is more likely to actually happen if all those players can find a way to complement each other’s strengths (if not agree on ideology). Broad-based political cooperation in the service of shifting the political center back away from the Right remains an elusive goal for, but one worth thinking hard about.

The size, strength and longevity of the American Right asks even tougher questions about radicals’ visions for any sort of long-term revolutionary transformation. In the wake of the end of the Cold War, left radicals have gravitated away from traditional Marxist concepts like “dictatorship of the proletariat,” and developed more interest in non-authoritarian revolutionary ideals. But if your goal is a society whose transformation requires the participation of all, and you live in a country where a durable third of the population sincerely holds deeply reactionary ideas, anarchism begins to look even more impractical.

And if something as mild as Obama’s healthcare plan is rabidly attacked as a socialist seizure of power by the Right, can you imagine their response to any future moves that actually did go in the direction of true economic democracy? Tea Party or otherwise, the Right will be with us in the millions for the foreseeable future, and in the US their genuine strength makes a mockery of the Left’s hopes for reform or revolution. To contradict one feel-good slogan—they’ve got the guns and we, well, we don’t even really have their numbers.

Jim is a union organizer with a background in global AIDS and anti-war activism. He can be reached at rustbeltjacobin (at) gmail.com